Two long, but utterly fantastic reads on the subject of football financials from the Independent, and why the big clubs are getting bigger and bigger.

How modern football became broken beyond repair

The game is going through an unprecedented period of financial and competitive imbalance. Miguel Delaney investigates how we got here and – crucially – whether the dominance of the mega-rich is here to stay

“We don’t want too many Leicester Citys.”

These were the words spoken by a senior figure from the Premier League’s ‘big six’ clubs, in the kind of high-end London hotel you can easily imagine.

“Football history suggests fans like big teams winning,” the official continued, to the group of business people and media figures present. “A certain amount of unpredictability is good, but a more democratic league would be bad for business.”

Exactly whose business would it be bad for? And why is football even viewed that way? The answers are among the biggest problems for the game right now.

That big-six representative need not have worried. The entire sport has been increasingly conditioned so that Leicester City situations – where a club from outside the financial super elite actually wins a major title – are close to impossible. This is why the odds in 2015-16 were so long and that story was so exceptional. Let no one tell you, as former Real Madrid president Ramon Calderon insisted to The Independent, that “football has always been like this”.

He’s wrong. It hasn’t.

Every metric indicates that it is at a far worse level than ever before. It is getting worse and threatening to become irretrievable.

As this investigation will reveal, football’s embrace of unregulated hyper-capitalism has created a growing financial disparity that is now destroying the inherent unpredictability of the sport. This is not just the big clubs often winning, as has been the case since time immemorial. It is that a small group of super-wealthy clubs are now so financially insulated that they are winning more games than ever before, by more goals than ever before, to break more records than ever before. They are stretching the game in a way that has caused the entire sport to transform and shift.

That is a consequence of the explosion of money in the game, which means you need a minimum amount of annual revenue (€400m in 2020, going by Deloitte’s figures) to even begin competing. On the other side, when clubs like Liverpool or Manchester City maximise that revenue through admirable intelligence, the disparity then has an amplifying effect. The gap gets even greater on the pitch. This is why we are seeing so many historic records now being broken season after season.

The last decade alone, which represents the true rise of the super-clubs alongside the huge rise in money, has seen:

a second Spanish treble

a first German treble

a first Italian treble

a first English domestic treble

three French domestic trebles in four years

a first Champions League three-in-a-row in 42 years

the first ever 100-point season in Spain, Italy and England

‘Invincible’ seasons in Italy, Portugal, Scotland and seven other European leagues

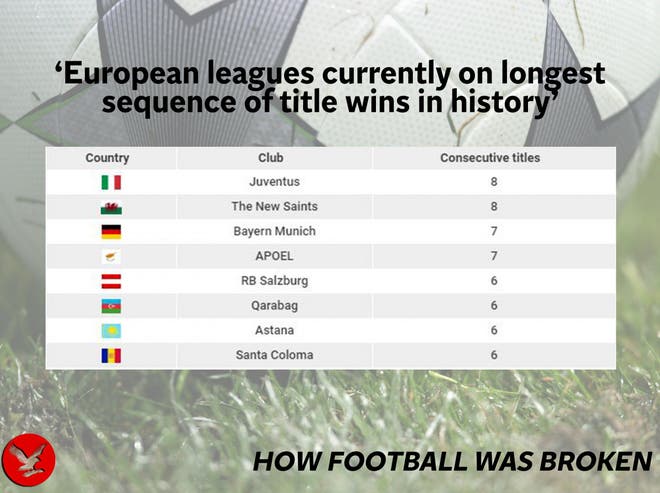

13 of Europe’s 54 leagues currently seeing their longest run of titles by a single club or longest period of domination.

Many of these feats appeared to be impossible for decades. They have now all taken place around the same time in the last decade, with the prospect of more to come. Needless to say, they have all been achieved by the wealthiest clubs in those competitions.

The concentration of money has brought a concentration of quality and thereby success.

This is not to say there won’t be outliers, like the underwhelming seasons recently suffered by Manchester United or Arsenal, or the unexpected triumphs of clubs like Leicester City.

Humans are involved, so there will be fluctuations and rises and dips.

Long-term trends don’t bring total uniformity. That’s not how they work.

To point to such exceptions as counter-arguments is the football equivalent of using a few cold days to dismiss global warming.

The wider trends are beyond debate.

They are also causing huge debate at the very top of the game.

Growing fears

Uefa president Aleksander Ceferin made the issue front and centre of his introduction to the body’s 2020 annual benchmarking report, citing the “threats” and “risks” of “globalisation-fuelled revenue polarisation”.

And it really comes to something when Deloitte’s Football Money League – as bombastic a celebration of wealth in the game as you could have – warns of “a situation where on-pitch results are too heavily influenced by the financial resources available” as well as the danger to “the integrity” and “unpredictability” crucial to the long-term value of the sport.

Javier Tebas, president of La Liga, speaks in even graver terms. “If we don’t fix that problem, in a few years our industry will collapse.”

It is teetering on the brink because this core problem loads up so many other ongoing issues: the precarious financial health of clubs outside the elite; the tension between the super-clubs and the rest; the tension between leagues; the tension between Uefa and Fifa; the tension between self-interest and the collective that represents the inherent contradiction of professional sport.

The Independent has been told this problem of financial disparity is at the core of ongoing debates about the structure of the football calendar, an issue that has exploded in the last month, with one high-level source speaking even more starkly.

“We have to stop the trend now. The gap is growing exponentially every season. It’s now or never. We can potentially destroy the world ecosystem of football.”

That “ecosystem” is right now very finely balanced, but nowhere near as finely balanced as the very nature of football itself and how the game is actually played.

This is what must be understood in regard to the core unpredictability of the sport being eroded by money.

Football has famously always been the game that anybody can play, with matches anyone can win. The preciousness of a goal has ensured it is just low-scoring enough to strike the perfect balance between satisfying reward for performance and the right amount of surprises. The fortuitous positioning of the penalty spot perfectly reflected this. Its distance gives a 70% chance of scoring, exactly the right ratio between punishment and possibility of missing.

That has generally been translated into wider results for the majority of the game’s history, so there have been spells where Bayern Munich’s league titles have been punctuated by victories for clubs like Kaiserslautern, Werder Bremen and Wolfsburg.

Football, as Johan Cruyff once said, is “a game of mistakes”. That is where its unpredictability lies. That is what the embrace of hyper-capitalism is eroding.

An 11-strong group of what Uefa describe as the “most global” clubs have reached a size where mistakes are less and less likely.

It makes a Dejan Lovren error against Shrewsbury Town stand out all the more, and any upsets stand out all the more, because they are so rare.

“There will maybe be the odd surprise, but this is how it’s developing,” former Southampton executive chairman Nicola Cortese says. “These bigger clubs are now massive money monsters.”

Due to the sport’s very structure, its immense global popularity has actually funnelled more and more resources to an extremely narrow band of clubs, because they are the only ones with the reach to maximise this.

It is not so much the 1%, as the 0.01%.

And it is not that money guarantees success. It is that an awful lot of it – in 2020, around €400m – is the single most important requisite to even compete.

The economics and the effect

In order to grasp just how great the shift in the game has been, it’s worth going back to quainter times. That is as recently in history as the 1980s, when the processes that led to all of this properly began.

This was a period when, as many attest, football was “barely running as a for-profit business at all”.

An all-conquering Liverpool were running the game, but this was domination of a more organic nature to now. There just wasn’t enough money in the game for it to be such a factor. The 1982 English First Division TV deal was just £5.2m and the total international rights were a mere £50,000 from Scandinavia. The wage bill of the wealthiest top-division club was less than three times the bottom club, which meant there was a period when two of the best paid players in England – Michael Robinson and Steve Foster – both played for Brighton and Hove Albion.

It also meant that as many as 13 clubs could finish in the top four in England, as many as 12 in Spain, and that teams including Aston Villa, Steaua Bucharest, PSV Eindhoven and Red Star Belgrade could win the European Cup.

Football, in effect, was too small an industry to feature anything like the current inequalities. There was far more mobility within the sport.

That was to dramatically change.

The bare figures are enough to explain why.

The total Premier League TV rights for the current 2019-22 cycle are now worth £8.4bn. The total Champions League prize money is now worth €2.04bn, having grown from €583m just 10 years ago. Such forces have seen Manchester United go from a turnover of £117m at the start of the millennium to £627.1m in 2018-19, the most recent figures available.

The biggest clubs are no longer the financial size of local supermarkets, as was the case just two decades ago.

The size of the game has totally transformed. As David Goldblatt relays in his superb book, The Age of Football, the sport in Europe now turns over more revenue than the continent’s publishing or cinema industries.

Money has been the great differential.

More money, however, has simply led to more disparity.

Returning to wages, the ‘stretch’ from the bottom to the top in the Premier League has gone from 2.85x in that breakaway season of 1992-93 to 4.7x last year. In Spain, it has been as high as 17.2x, and in some mid-size leagues like Switzerland over 20x.

This is relevant because of how crucial wages are to the working of the sport. Repeated studies – most notably by Stefan Szymanski and Tim Kuypers – have highlighted that they condition results to a greater degree than anything else. Arguments about net transfer spend are close to irrelevant.

“Buying the most expensive players doesn’t automatically generate good sporting results,” Manchester City chief executive Ferran Soriano wrote in his book The Ball Doesn’t Go In By Chance. “What does generate those good results is having the best players in your team and paying them the salary they deserve.”

This is what really creates the stretch.

“I had the money to buy players,” Cortese says. “But not the money to keep players.”

This has been the primary issue for most Premier League clubs seeking to grow, despite the influx of TV money that has allowed high transfer fees.

By the competition’s latest figures, the big six paid 51.3% of the total wages.

This disparity has led to a corresponding disparity in results. And thus the unpredictability of football – the lifeblood of the sport – begins to dissolve.

Put together here for the first time, these figures say even more, and paint quite a staggering picture.

Absolutely every metric shows the sport across Europe is more predictable than 30, 20 or even 10 years ago.

You can start at the very top.

The average points won by champions in the five major leagues has shot up.

England might only show a marginal change from the 2000s to the 2010s, but the change becomes much more pronounced if you focus on the last three seasons. It then extends to 96.7 points – and that’s before you even bring in Liverpool’s current season.

Many might fairly put that down to the standard raised by managers like Pep Guardiola and Jurgen Klopp. But they are paid handsomely too. They are part of the same force. What these rises in top points tallies really represent, going by the correlation between wage and league finishes, is that the wealthiest clubs are simply winning more games.

Greater disparity has pushed up the requirements to win the league. That can be seen in the most ominous figures of all: the title-winning streaks. In some leagues, it is getting impossible for almost anyone else to win.

Prior to this run, Bayern Munich had never won more than three Bundesliga titles in a row. They have now won seven in a row, which is by far the longest streak of league victories in Germany’s history. It is also one of eight such situations across Europe.

There are then situations like in Croatia, where Dinamo Zagreb have won 13 of the last 14 titles, or Dundalk, who have won five of the last six Irish titles. There has never been a situation where so many of Europe’s leagues – 13 of 54 – are suffering such domination at the same time.

That it extends from the very top, to mid-sized leagues like the Austrian Football Bundesliga, to the bottom and the Andorran Primera Divisió, shows the depth of the problem.

It also shows the effect of Champions League prize money, which has become one of the most profound problems in the game, as influential as anything else in creating this disparity.

The difficulty in qualifying for the competition, of course, is just another representation of that disparity.

That is emphasised by the fact more clubs finished in England’s top four in the first five years of the 1990s than in the 20 years so far of the new millennium: 11 to 10. The number for 2010 to 2019 as a whole is seven, down from 13 in the 1990s and 1980s, and 15 in the 1970s and 1960s.

The other major leagues tell a similar story, and that without a defined big six.

Just as with the title race, meanwhile, increased wealth has also increased the points threshold for qualification to the Champions League.

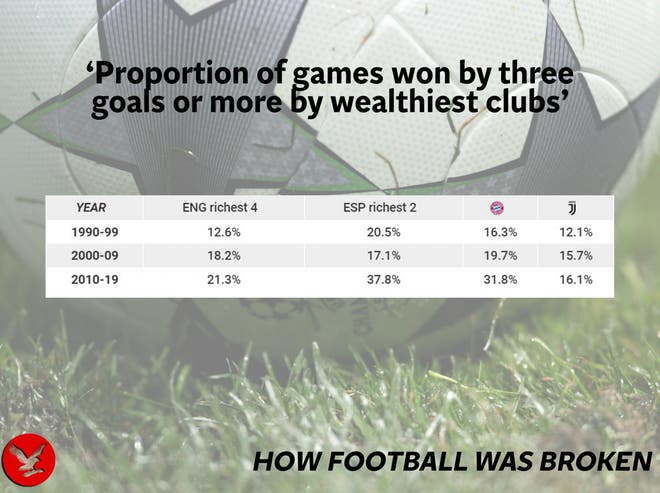

It is not just that the wealthiest clubs are winning much more, however. It is that they are winning by much more.

So many clear victories are perhaps the clearest indication of the ‘Overton window’ effect of this: where gradual shifts over time make abnormal situations feel normal to anyone watching on. Thrashings of the scale the wealthiest clubs now dole out – Manchester City beating Watford 8-0 or Bayern Munich beating both Mainz and Werder Bremen 6-1 this season – used to be so much rarer. Even 5-0 thrashings were comparatively uncommon.

Looking at England’s wealthiest four clubs – which has varied since the start of the Premier League – over a fifth of their games are now won by three goals or more. For the 90s, that was just over a tenth, at 12.6%.

This is most pronounced with Spain’s big two, who are always cited as the eternal victors. “Así gana el Madrid” is the chant, meaning “That’s how Madrid win”. It refers to how, no matter what happens in a game, they always find their way.

But even the mighty Real Madrid did not used to win like this. Together with Barcelona, their percentage of wins by three goals or more has jumped from 20.5% in the 90s, to a staggering 37.8% now.

The shift in football as a whole is now undeniable.

It is simply blinkered to say that it has ‘always been like this’.

Even Soriano argues in this book that “the classic ‘that’s football!’ argument” defies both logic and evidence”.

It has never been this bad. And it might yet get even worse. The forces that led us to this are as important as the effects.

How it got here, and where it’s going

The 14 other Premier League clubs were at first taken aback. Then the feeling that they were being taken for a ride began to grow.

Their representatives were at a meeting to discuss the competition’s international TV rights distribution and, in putting forward the position of the big six, Daniel Levy just kept using the same five words: “We only want what’s fair.” As Joshua Robinson and Jonathan Clegg’s book The Club details, the Tottenham Hotspur chairman repeated it to every single objection.

The argument was that the ‘big six’ are the clubs who bring all the international attention – and so they therefore deserve more of the money. The counter-argument is obviously that they need teams to play against, and that the attractive founding principle of the Premier League is equality.

The great complication is that the following cycle: the more money the ‘Big Six’ receive, the better they become. The more attractive they are to audiences. The better commercial deals they can strike. The better they become. And the more attractive they are. Thus strengthening a self-perpetuating cycle that just keeps on increasing the gap.

The leverage – of course – is another break-away.

“They’ve been using the threat of the super league for 20 years now,” one high-level source says. “Every time there is a discussion about revenue distribution, they put it on the table.”

This dilemma – still live and present in the game and growing – is a microcosm of the wider situation that has led football to the brink.

The game has been engulfed by capitalism, yes, but the compounding issue is that the most influential stake-holders have so fully embraced this.

There has been almost no resistance or regulation, which in itself has added multiple layers of self-perpetuation. The belligerence of the big clubs has been a huge part of it. This is why the problem is threatening to get worse.

A massive issue, as Goldblatt argues to The Independent, is that inequalities were already “hard-wired into the global football infrastructure” before the game’s authorities even realised the need to do something about it.

The initial re-wirings were, of course, nakedly capitalist.

The first in England was almost symbolic, as it came at the very height of Thatcherism in 1983. The FA at that time had in place a 19th-century regulation called Rule 34, which at least acknowledged clubs were a social institution. Rule 34 prohibited directors from being paid and restricted dividends to shareholders.

Seeking to become the first club to float on the stock market, Tottenham Hotspur and their advisors asked if they could form a holding company to evade the restrictions of Rule 34. The FA did not object. Instead they waved it through. This was accompanied by the mid-80s change to gate-money distribution, which saw home teams receive bigger proportions, inherently loading more towards the biggest clubs.

“The fact football associations – with pretty much the exception of the Germans – have waved all of this through has been a huge factor,” Goldblatt says.

By then, though, financial influence was moving from the stands to somewhere without fences or potentially any limits at all. Broadcasting.

Silvio Berlusconi’s takeover of AC Milan in 1986 gave him the entry-point to bring his private broadcasting ideas to football, which revolutionised the way TV was thought about in the sport. The Italian mogul saw the game as a potential “world-wide television spectacular”, with that potential wasted on parochial ideas. He felt it absurd that the biggest clubs were not regularly meeting in glamorously lucrative matches.

Berlusconi sought to force the issue through a commission for the first European super league.

Uefa rejected the idea, but the die had been cast. The first Champions League, in 1992-93, incorporated many of the same ideas, right down to branding and an anthem.

It is no coincidence the Premier League was launched at the same time, influenced by the same ideas and driven by the same motivation: money.

“People think there must be a lot of thinking in this Premier League,” the late Graham Taylor said at the time. “There is none … I think a lot of this is based on greed.”

It should not be overlooked that the decrepit nature of football in the 1980s – which ultimately descending into real-life tragedies such as Heysel and Hillsborough – made so much of this necessary. The game badly needed updating and badly needed the funding to do so, as well as ways to raise that funding.

Better broadcasting deals through glossy competitions therefore never had a more persuasive argument. The problem is how far it went the other way. The ruinously decrepit gave way to the gleamingly decadent.

“Once the Premier League and Champions League set their model, everybody else is following one way,” Goldblatt says. “These competitions began life when nearly all the economic safeguards and regulations have been dismantled.”

Just as internal protections were stripped away, meanwhile, the game was further opened up by external forces.

Among the greatest was the fall of Communism, which meant Eastern Bloc nations such as Poland and Ukraine were unable to keep star players within their borders. There was then the influence of the European Court of Justice, and the 1995 Bosman ruling. This immediately made players free agents once their contract ended and also prohibited EU member states and Uefa from imposing quotas on foreign players. Soriano said it “shook the market”. In reality it created a new one: a massive labour market that – according to Goldblatt – is more “global than banking”.

“Even Serie A still only allowed three foreigners per squad. Three Dutchmen at Milan was considered unbelievably cosmopolitan. Now, that’s nowhere near as cosmopolitan as Bournemouth.

“Bosman and the creation of a global labour market has been incredibly important. It also generated the creation of a global network and system of agents and scouts.”

One key factor was that its very globality made it impossible to regulate.

“Look at agent regulation,” football finance expert Kieran Maguire explains to The Independent. “Fifa said in 2016 we can’t monitor what’s happening in 200 countries so we’re just going to abandon the whole project. They’ve effectively done that in terms of the democratisation of the game.”

It created yet another mechanism of self-perpetuation. One that was to eventually be driven by the biggest mechanism of all: the Champions League.

It is this tournament that has perhaps more than anything created this minimum financial threshold.

The competition has become so popular that its prize money is simply immense: life-changing for many clubs and game-changing for the sport as a whole. It is so drastic that it distorts football.

Merely turning up in the group stage this season earned clubs €15.25m. Getting to the Istanbul final will be worth €62.25m – and that’s before you factor in many related rewards. The near £100m Spurs earned last season was enough to launch them past Chelsea into the top 10 of the Deloitte Football Money League.

“The Champions League has been a closed shop for the majority of the last decade,” Maguire says. “A figure like £100m allows you to buy an awful lot of wages, to invest. So, all of a sudden, if you want to challenge them, you’ve got to find £100m and that’s just for one season.”

That, by coincidence, is the figure Jack Walker pumped into Blackburn Rovers to make his club Premier League champions in 1994-95 by financial brute force. It would now barely make a dent.

“This is the big difference,” Goldblatt says. “Nottingham Forest didn’t turn into an economic powerhouse by winning it twice, whereas now it catapults you into a completely different economic zone. We’ve seen this with smaller European nations, where one club manages every year to get to the qualifying stages – not even the group stages – and that’s enough to give them an unbeatable head start.”

It is a source of so many of these spells of domination: from Austria to Andorra.

“The impact on smaller leagues has been absolutely dramatic,” one Uefa source says. “It also makes them less attractive to domestic audiences, turning more and more people to the biggest leagues.”

The result? Another layer of self-perpetuation.

The ‘Everton problem’

The Champions League does much more, however, than creating this huge financial capital. It also creates a football capital – and what you might call the ‘Everton problem’.

It is just another way the game is so conditioned towards the richest. The massively free player market makes it a race to the top, where the richest are able to accumulate the best in a way never seen before. Every player obviously wants to be in such a competition.

This means that even if clubs like Everton have the money to pay competitive wages, they are still mostly getting cast-offs, a level of player short of the true elite. And when they do have a player who can perform at Champions League level, like Romelu Lukaku, he is quickly picked off.

The forces of the game just don’t allow clubs outside the elite the time and space to get to that level. There are too many ceilings to smash through, with so many layers of money on top. The excellent Swiss Ramble Twitter account has calculated that England’s big six have benefited from 93% of European TV money in the last eight years.

Some clubs – like Valencia and Leeds United – have attempted to break through this with huge investment, only to bring themselves close to ruin.

The introduction of Financial Fair Play (FFP) attempted to prevent this. But the legislation came too late. Rather than creating a necessary competitive balance in European football, it reinforced the pre-existing levels.

“Had Uefa introduced regulations like FFP 20 years earlier, I think it would have made a notable difference,” Goldblatt says. “And I think it would have been a deterrent to more egregious foreign owners who have lots of money and political aims.”

It was the glamour of the Champions League, after all, that first attracted Roman Abramovich to football. That set the trend for another factor that has transformed the finances of the game: takeovers from the mega-rich.

One potential solution to this would be revenue redistribution, in the form of “solidarity” payments. Discussions are ongoing at the start of 2020 to determine Uefa money towards clubs not participating in European competition for the 2021-24 cycle, so as to level the playing field.

But these discussions again involve the tension between those who generate the most interest, and the financial disparity that generates.

And it’s that same threat that has hung over any discussions: the prospect of a European super league. The result in the last discussion over solidarity payments? They actually decreased: from 8.5% to 7.3%.

“Solidarity for the non-participating clubs is the sole mechanism we have to protect competitive balance, and compensate for huge money,” one source says. “The big clubs are always pushing. Uefa is in a difficult position, as they need to find a balance, but it’s not easy.

“It usually ends up that they say we have to listen to the top clubs and give them something, to stop them going in the direction of a super league.”

This is the cycle the game is now in. The cycle that binds it. With every step of negotiation, a little more is ceded to the big clubs, which earns them even more revenue.

So it is with results. They shift a bit more towards the super-wealthy with every cycle. And so the differences between clubs become imperceptible and thrashings become so commonplace.

It is also why Uefa’s description of “global clubs” is so apt.

In this almost completely unregulated world-wide football market, there are only a few that traverse the planet in terms of supporter base and appeal. It allows them to grow to financial sizes that no other club can reach.

“For a club like Southampton, it was always difficult to attract top sponsors,” Cortese explains. “They are not going to go to a team who’s not playing international football. They want to put their money – and pay a lot of money – for the biggest audience.”

It was of course Manchester United who were the innovators in this regard, in two stages. There was first of all the carpet-bombing merchandising of the early 90s. That created what Soriano referred to as the “virtuous circle” in terms of how much money it allowed them to pump back into the team.

There was then the more sophisticated second stage under the Glazers, which involved dividing the globe into separate, distinct markets. This has been a huge influence for the top Spanish clubs, who willingly took on United’s model.

This is also the source of the Premier League’s ‘big six’ pushing for a greater proportion of the international broadcast rights. And, in another landmark moment in 2018, they got their wish.

That is their platform: the entire planet.

Only a handful of clubs – Manchester United, Barcelona, Real Madrid, Liverpool, Arsenal, Juventus, Bayern Munich, AC Milan and Internazionale – are capable of truly benefiting from it. They just have a distinctive global fan base, and thereby a ready-made market, that is impossible for anyone else to replicate. Anyone else – such as Manchester City, Chelsea and Paris Saint-Germain – needs a takeover.

It is why, in imploring John Henry to buy Liverpool in an email in 2010, Boston Red Sox employee Joe Januszewski wrote that Liverpool would represent “the deal of the century” and are “just begging to be properly marketed and leveraged globally among the soccer-mad masses”.

That has now happened.

All of these factors began to properly coalesce around 2010 to just put this distinctive group of clubs on another level, that was only going higher. It fundamentally changed what they are.

“The growth of the third source of income culminates in a fundamental change of model, which converts the football club business into a global entertainment business,” Soriano wrote. “This is the point where the big football club ceases to resemble a local circus and becomes more of a Walt Disney.”

They are no longer just football clubs. They are glamorous content providers.

This is why “more Leicester Citys” simply are not appealing to them. It’s not good for their own content. Soriano effectively admitted this view in his book.

“A well-known American sports manager once said to me: ‘I don’t understand why you don’t see that what you should be doing is boosting teams like Seville FC and Villarreal FC to make the Spanish league more exciting and maximise income’. While I was listening to him, I found it very difficult to think about maximising any income of any kind, because all I wanted and cared for was for FC Barcelona to win all the matches and always win, independently of the ‘tournament overall income’ or suchlike concepts.”

Calderon put it in more basic terms for The Independent, when he was asked whether football has embraced capitalism more than any other industry.

“Well, maybe, maybe. I think that it’s something you can’t avoid. Football has become show business. The stadiums are big TV sets, where 22 performers are performing. It’s show business, in some ways, more than sport.”

But show business doesn’t really care for the smaller theatres.

Calderon also set out the rather naked view of the big clubs. “That’s life,” he simply said.

But need it be?

This is the tension at the heart of the game, the big question. And this is the contradiction between self-interest and collaboration in professional sport.

“I look at the big clubs and their endless desire for money and I just think… what’s the point?” Goldblatt laments. “It’s not like you’re making much of a profit here. So what are you doing it for? What is the point of this death spiral of an ever-smaller number of clubs fighting it out?

“I really do think that these people running the clubs are locked into a way of thinking that is sort of self-destructive and they justify themselves by saying we must have more money so we can have better teams so we can have better product… but for what?

“In every other economic sector, people try and take their competitors over, but obviously that doesn’t happen in football.

“People think the unit of analysis is the club, but actually the game as a whole should be the unit of economic analysis. It’s the mad dynamic of capital accumulation, and it’s ultimately very odd that a very small number of people should be driving what is a collective experience for millions of people.”

One exasperated source goes even further.

“We cannot allow the football eco-system to be destroyed in the interests of a small group of clubs. It is much more than money at stake here. We should all recall the social value of football, the role it plays in communities.

“We have a super-rich, but we are destroying the base. The top clubs are not really understanding what is at stake.”

It all means that, right now, it feels like there’s less at stake in many games. They’re decided far too early. Their outcomes are far too predictable.

The wonder is what can be done about it?

https://www.independent.co.uk/sport...l-man-utd-barcelona-real-madrid-a9330431.html

---------------------------

What can we do to save football?

In the second part of his investigation into the health of the modern game, Miguel Delaney asks what can be done to counter the growing financial and competitive imbalance of the sport

At the very top of European football right now, discussions are going on that are a lot tenser than many of its highest-profile matches.

The issue up for discussion is the distribution of revenue towards clubs not involved in Uefa competition, called “solidarity” payments, which are one of the game’s only mechanisms for limiting growing financial gaps.

On one side, a source within the super clubs says they believe one particular idea for the 2021-24 cycle is “extreme”. On the other side, the European Leagues group – which covers the domestic competitions – is described as “exasperated”.

The huge difference in stances illustrates the difficulty of all this.

The current solidarity figure is 7.3% – of over €2bn – that is to be distributed among the thousands of clubs not participating in either the Champions League or Europa League. For many outside the elite, this is nowhere near enough, and represents a mere sop that actually only sees immense disparities increase. The European Leagues want it raised to 20%.

“The big clubs,” one source says, “would laugh that out of town”.

They can do that because they’ve got serious heft. That 7.3%, after all, is actually a decrease from 8.5% in the previous cycle. It’s the usual story. Every such decision usually sees a bit more go to the wealthiest and less for everyone else, until you suddenly find yourself staring at a chasm.

It is this process – and the accompanying tension – that encapsulates the difficulty of trying to solve football’s hugely destructive financial disparity.

The game must first figure out how to stop this problem getting worse, before it can then attempt to row it back.

That is not easy when the biggest clubs, and biggest voices, are so sternly pushing in the opposite direction. Every cycle of decisions generally just sees more ceded to their interests, in large part due to the ever-present threat of a super league.

As football historian David Goldblatt says, “it’s all flowing one way”. Finance expert Kieran Maguire agrees. “It is going to go further. The differences are going to grow.”

So, can anything actually be done about this? Are there any realistic solutions?

Many influential voices spoken to for this article were at a loss because of how lopsided the structure of the game is.

Most put forward some form of redistribution, since it is the most workable and effective. That is also what makes these discussions about solidarity payments so galling.

They are one obvious step, and should be the most easily applicable step since it is Uefa money as opposed to that generated by domestic league TV rights. But there’s still such attrition over it.

At the same time, more equitable TV rights makes a huge difference, as the Premier League has proven for most of its existence. That is why the slight change in international rights feels another line in the sand.

Javier Tebas, president of La Liga, is meanwhile looking to row things back there.

“I don’t think we are helping football in any way if we generate wealth and it just goes straight back to the big clubs, but that’s what’s happening.”

Goldblatt strikes a similar tone.

“In the same way as in the global economy, the rich are able to accumulate and accumulate. In the absence of redistributive systems – in the form of taxation on benefits or whatever – the poor are getting poorer, even in the richest countries.

“Imagine if the Premier League was redistributing 20% of its TV income around the game. Grassroots football in this country would be in a very, very different state.”

The brutal reality of the state of the game, however, is that the gaps are so vast that the sport really needs some kind of Das Kapital-style financial revolution. This, needless to say, would get more than laughed out of town. It would simply be unpalatable to super-clubs now so committed to the game’s systemic capitalism.

This is all the more lamentable since these are still mere negotiating positions, for the most workable solutions, that should be malleable. The problem with almost every other potential solution is that there are by now huge structural and technical impediments.

Every turn just sees another brick wall.

It is why Financial Fair Play came 20 years late, as Goldblatt points out.

“I think that was the moment in the early 90s. By the time Uefa have finally, finally got to FFP in 2012, these inequalities are hardwired into the system.”

It similarly means, as Maguire argues, that modern FFP mostly just “reinforces the glass ceilings within the game”.

Take the idea of a US-style salary cap, and the challenge of applying it at different levels. Most of the formulae it would be based on would still inherently favour the wealthiest. There’s then the potential of Bosman-style legal challenges within the European Union, as well as how difficult it is to apply on a global level. If there’s any kind of gap, due to the idiosyncrasies of a few countries, the whole system crashes down as there’s that space in the market. It’s only possible with US sports because they are so centralised in single organisations.

“This salary threshold in Europe is obviously not allowed,” Tebas says. “It’s a case of [global] supply and demand and that’s what salaries are based on. I’m not sure a salary cap is really the issue here.”

Goldblatt argues an idealised solution is the spread of Germany’s 50+1 rule ensuring majority social ownership of clubs. Sweden has followed the Bundesliga’s example, and that has created one of the few leagues where there is huge competitive balance and internal mobility.

“The compensation for economic modesty is a more diverse football culture,” Goldblatt argues, in a line that pretty much sums up modern football history.

There are similarly a few blocks to this, though, that build up to one big issue.

There’s first of all the question of getting clubs to make that drastic first step that willingly sets them back behind other countries for a few years. As with everything else, you need everyone to go along.

There’s then the more complicated issue of clubs within your own country – like Bayern Munich – who are already much bigger than everyone else. The danger is a 50+1 rule freezes movement.

Above anything else, though, there’s the issue of the existing owners.

Capitalists like the Glazers or Fenway Sports Group aren’t just going to give up chunks of Manchester United or Liverpool.

A sportswashing project like Abu Dhabi isn’t just going to give up chunks of Manchester City.

Such moves would be entirely contradictory to their intentions. Which is why such steps to any kind of fairer system – to go with the rest of the big clubs – are so difficult to extract.

Consider a figure like Florentino Perez. He sees everything in terms of the glory of Real Madrid, and – more importantly – how it will reflect on him as president. Gestures to redistribution may affect the ability to sign more Galacticos.

Ferran Soriano expressed a similar view in his book, when at Barcelona. It is a line that is worth repeating, because it is so central to the problem.

“A well-known American sports manager once said to me, ‘I don’t understand why you don’t see that what you should be doing is boosting teams like Seville FC and Villarreal FC to make the Spanish league more exciting and maximise income. While I was listening to him, I found it very difficult to think about maximising any income of any kind, because all I wanted and cared for was for FC Barcelona to win all the matches and always win, independently of the ‘tournament overall income’ or suchlike concepts.”

Against that, fans can take individual action.

There is the drastic step of not contributing to this system; to refuse to buy the broadcasting subscriptions; to refuse to go to games.

That still feels like it’s asking far too much of people so emotionally invested in this, and like blaming individuals for a system way beyond them. This should still be on the main stake-holders in this system, and those who are meant to safeguard it. These are the ones driving it. The major clubs and bodies are taking conscious decisions and stances that should be scrutinised.

It is on them.

In Europe, Uefa does have an impossible balance to strike between safeguarding the game and managing the objectives of the big clubs, but the current dynamic is that more is always ceded to the latter. This needs to stop. It needs strength.

There is something more practical individual fans can do, too. They can invest more time in their local teams. One of the huge problems inherent to this is the global mass of supporters that the 11 biggest clubs are developing, at the expense of everyone else. It is a huge factor in disparity. It instantly denies more local clubs of ticket sales, sponsorships, TV viewers and basic interest. This has been especially ruinous in African countries and Ireland, given the obsessive interest in the Premier League.

Such glamour is obviously hugely seductive, and the obvious source of this disparity, but can still warrant initiative from those who truly love the game and what it means.

Otherwise, more and more will go to the super clubs.

Nicola Cortese even sensed similar issues when he was working at Southampton. “Manchester United’s biggest fanbase is in Asia, and they would much rather see Manchester United against Real Madrid than Manchester United against us.”

It is also why there has been such a growing crisis over the football calendar, with more to come.

The big clubs only want to play in the most attractive matches, against fellow glamour clubs. They don’t really care for fixtures – like inconvenient domestic cup replays or second legs – that don’t generate the same money.

At the very top of European football right now, discussions are going on that are a lot tenser than many of its highest-profile matches.

The issue up for discussion is the distribution of revenue towards clubs not involved in Uefa competition, called “solidarity” payments, which are one of the game’s only mechanisms for limiting growing financial gaps.

On one side, a source within the super clubs says they believe one particular idea for the 2021-24 cycle is “extreme”. On the other side, the European Leagues group – which covers the domestic competitions – is described as “exasperated”.

The huge difference in stances illustrates the difficulty of all this.

The current solidarity figure is 7.3% – of over €2bn – that is to be distributed among the thousands of clubs not participating in either the Champions League or Europa League. For many outside the elite, this is nowhere near enough, and represents a mere sop that actually only sees immense disparities increase. The European Leagues want it raised to 20%.

“The big clubs,” one source says, “would laugh that out of town”.

They can do that because they’ve got serious heft. That 7.3%, after all, is actually a decrease from 8.5% in the previous cycle. It’s the usual story. Every such decision usually sees a bit more go to the wealthiest and less for everyone else, until you suddenly find yourself staring at a chasm.

It is this process – and the accompanying tension – that encapsulates the difficulty of trying to solve football’s hugely destructive financial disparity.

The game must first figure out how to stop this problem getting worse, before it can then attempt to row it back.

That is not easy when the biggest clubs, and biggest voices, are so sternly pushing in the opposite direction. Every cycle of decisions generally just sees more ceded to their interests, in large part due to the ever-present threat of a super league.

As football historian David Goldblatt says, “it’s all flowing one way”. Finance expert Kieran Maguire agrees. “It is going to go further. The differences are going to grow.”

So, can anything actually be done about this? Are there any realistic solutions?

Many influential voices spoken to for this article were at a loss because of how lopsided the structure of the game is.

Most put forward some form of redistribution, since it is the most workable and effective. That is also what makes these discussions about solidarity payments so galling.

They are one obvious step, and should be the most easily applicable step since it is Uefa money as opposed to that generated by domestic league TV rights. But there’s still such attrition over it.

At the same time, more equitable TV rights makes a huge difference, as the Premier League has proven for most of its existence. That is why the slight change in international rights feels another line in the sand.

Javier Tebas, president of La Liga, is meanwhile looking to row things back there.

“I don’t think we are helping football in any way if we generate wealth and it just goes straight back to the big clubs, but that’s what’s happening.”

Goldblatt strikes a similar tone.

“In the same way as in the global economy, the rich are able to accumulate and accumulate. In the absence of redistributive systems – in the form of taxation on benefits or whatever – the poor are getting poorer, even in the richest countries.

“Imagine if the Premier League was redistributing 20% of its TV income around the game. Grassroots football in this country would be in a very, very different state.”

The brutal reality of the state of the game, however, is that the gaps are so vast that the sport really needs some kind of Das Kapital-style financial revolution. This, needless to say, would get more than laughed out of town. It would simply be unpalatable to super-clubs now so committed to the game’s systemic capitalism.

This is all the more lamentable since these are still mere negotiating positions, for the most workable solutions, that should be malleable. The problem with almost every other potential solution is that there are by now huge structural and technical impediments.

Every turn just sees another brick wall.

It is why Financial Fair Play came 20 years late, as Goldblatt points out.

“I think that was the moment in the early 90s. By the time Uefa have finally, finally got to FFP in 2012, these inequalities are hardwired into the system.”

It similarly means, as Maguire argues, that modern FFP mostly just “reinforces the glass ceilings within the game”.

Take the idea of a US-style salary cap, and the challenge of applying it at different levels. Most of the formulae it would be based on would still inherently favour the wealthiest. There’s then the potential of Bosman-style legal challenges within the European Union, as well as how difficult it is to apply on a global level. If there’s any kind of gap, due to the idiosyncrasies of a few countries, the whole system crashes down as there’s that space in the market. It’s only possible with US sports because they are so centralised in single organisations.

“This salary threshold in Europe is obviously not allowed,” Tebas says. “It’s a case of [global] supply and demand and that’s what salaries are based on. I’m not sure a salary cap is really the issue here.”

Goldblatt argues an idealised solution is the spread of Germany’s 50+1 rule ensuring majority social ownership of clubs. Sweden has followed the Bundesliga’s example, and that has created one of the few leagues where there is huge competitive balance and internal mobility.

“The compensation for economic modesty is a more diverse football culture,” Goldblatt argues, in a line that pretty much sums up modern football history.

There are similarly a few blocks to this, though, that build up to one big issue.

There’s first of all the question of getting clubs to make that drastic first step that willingly sets them back behind other countries for a few years. As with everything else, you need everyone to go along.

There’s then the more complicated issue of clubs within your own country – like Bayern Munich – who are already much bigger than everyone else. The danger is a 50+1 rule freezes movement.

Above anything else, though, there’s the issue of the existing owners.

Capitalists like the Glazers or Fenway Sports Group aren’t just going to give up chunks of Manchester United or Liverpool.

A sportswashing project like Abu Dhabi isn’t just going to give up chunks of Manchester City.

Such moves would be entirely contradictory to their intentions. Which is why such steps to any kind of fairer system – to go with the rest of the big clubs – are so difficult to extract.

Consider a figure like Florentino Perez. He sees everything in terms of the glory of Real Madrid, and – more importantly – how it will reflect on him as president. Gestures to redistribution may affect the ability to sign more Galacticos.

Ferran Soriano expressed a similar view in his book, when at Barcelona. It is a line that is worth repeating, because it is so central to the problem.

“A well-known American sports manager once said to me, ‘I don’t understand why you don’t see that what you should be doing is boosting teams like Seville FC and Villarreal FC to make the Spanish league more exciting and maximise income. While I was listening to him, I found it very difficult to think about maximising any income of any kind, because all I wanted and cared for was for FC Barcelona to win all the matches and always win, independently of the ‘tournament overall income’ or suchlike concepts.”

Against that, fans can take individual action.

There is the drastic step of not contributing to this system; to refuse to buy the broadcasting subscriptions; to refuse to go to games.

That still feels like it’s asking far too much of people so emotionally invested in this, and like blaming individuals for a system way beyond them. This should still be on the main stake-holders in this system, and those who are meant to safeguard it. These are the ones driving it. The major clubs and bodies are taking conscious decisions and stances that should be scrutinised.

It is on them.

In Europe, Uefa does have an impossible balance to strike between safeguarding the game and managing the objectives of the big clubs, but the current dynamic is that more is always ceded to the latter. This needs to stop. It needs strength.

There is something more practical individual fans can do, too. They can invest more time in their local teams. One of the huge problems inherent to this is the global mass of supporters that the 11 biggest clubs are developing, at the expense of everyone else. It is a huge factor in disparity. It instantly denies more local clubs of ticket sales, sponsorships, TV viewers and basic interest. This has been especially ruinous in African countries and Ireland, given the obsessive interest in the Premier League.

Such glamour is obviously hugely seductive, and the obvious source of this disparity, but can still warrant initiative from those who truly love the game and what it means.

Otherwise, more and more will go to the super clubs.

Nicola Cortese even sensed similar issues when he was working at Southampton. “Manchester United’s biggest fanbase is in Asia, and they would much rather see Manchester United against Real Madrid than Manchester United against us.”

It is also why there has been such a growing crisis over the football calendar, with more to come.

The big clubs only want to play in the most attractive matches, against fellow glamour clubs. They don’t really care for fixtures – like inconvenient domestic cup replays or second legs – that don’t generate the same money.

This is why the other ongoing discussion, about the post-2024 worldwide match calendar, is as important. Central to it are issues of financial disparity. Big clubs don’t necessarily want to play in the games that most benefit smaller clubs.

To go with all this, of course, Fifa are planning a hugely disruptive 24-team Club World Cup. The stated logic is to spread more money around the game. The implicit logic is however to compete with Uefa’s Champions League for earnings. The working logic is that they will have to pay the big clubs fortunes to get them and actually make it attractive, and that will only increase this financial disparity.

It is why many in the game now feel a lot of these forces are finally coming together to create that biggest line in the sand and another big change in the calendar – the launch of a super league.

“There are certain people at certain clubs who are thinking now might be the time,” one high-level source says. “A lot seems set up for it.”

Cortese agrees.

A super league has long been mooted, and never happened, but more seems in place for it than ever. The greatest issue of all is not that this is a good thing, or any way desirable. It is that it is a logical extension of this great disparity: lop off the big clubs to let them face each other; let everyone else work it out.

The great tragedy may well may be that this is the only actual solution.

That’s unless the biggest voices start to take responsibility. Otherwise, they could be responsible for the destruction of our game as we know it.

It would be massive change, from such a small group. It really shouldn’t come to this.

It’s our game. Not theirs.

https://www.independent.co.uk/sport...l-man-utd-barcelona-real-madrid-a9334826.html

Forum Supporter

Forum Supporter 10 years of FIF

10 years of FIF